Unleash Your Potential

June 23, 2022

Your Path to Leadership

October 12, 2022“Plans are Nothing. Planning is Everything”

General Dwight David Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, took another puff from a half-burned cigarette and then smashed it out in the ashtray, as if he was crushing out a dark thought. His decision would determine the fate of thousands of soldiers and, most likely, the outcome of the war. Several of the senior generals at the table wondered if Eisenhower would measure up to the task.

The time was 4 a.m., Monday, June 5, 1944. If the D-Day invasion was to take place on June 6, Eisenhower had to decide in the next few minutes. Eisenhower knew the fate of the invasion was his decision. He knew that he would have to roll the dice, make his play, and if he chose wrongly, thousands would die. A bloody failure of the invasion of France could extend the war for years.

Everyone at the table looked at Eisenhower. The clock ticked. The group waited for a decision. Eisenhower, known by his nickname “Ike”, put on his best poker face. He rose from his chair. All looked up at him, waiting for his decision. Ike warmed himself at the fire for a moment and then paced the room again in silence.

After a few minutes, he said, “Okay, Let’s go.” With those words, General Eisenhower launched the D-Day invasion. On June 6, 1944, in marginal weather, the Allies began the inevitable liberation of Europe from Nazi tyranny. It was one of the most difficult and courageous decisions of World War II.

It would have been understandable if Eisenhower delayed the decision to launch D-Day and waited for perfect weather. Without perfect conditions, the risk increased, but there are never perfect conditions. In business, fortunes are won or lost because CEOs make timely decisions. Eisenhower had more than fortune involved in his decision; he had the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and the fate of the free world in his hands.

The momentous problem-set that Eisenhower faced just before D-Day is unique, but all leaders face decisions, big and small. Learning from extraordinary cases is an excellent way to improve your ability to make decisions. Learning how to decide takes practice and how you decide will be the measure of your leadership.

Decision-making is vital to managers, supervisors, and especially, leaders. If a leader is exceptional at motivating. Decisions can be big and small, with either plenty of time to decide or very little. Major decisions are often stressful, enmeshed in bias, complex and uncertain.

Decisiveness is the key to effective leadership in any organization. It is helpful to categorize problems to help leaders navigate the future. Leaders must solve fresh problems every day. Many problems are unique and require original responses from leaders to solve unique problem-sets, but leaders can learn to recognize problems and sort them into three distinct groupings.

- Tame Problem Set

- Critical Problem Set

- Wicked Problem Set

One of my favorite authors concerning decision-making is Professor Keith Grint, Professor of Defense Leadership at Cranfield University, UK and Deputy Principal at the Defense College of Management and Leadership. He describes a tame problem as “Known problems with known solutions that are within existing expertise and know how. Tame problems are best approached from a management style of leadership, with a structured logical approach.”

Categories of Decisions

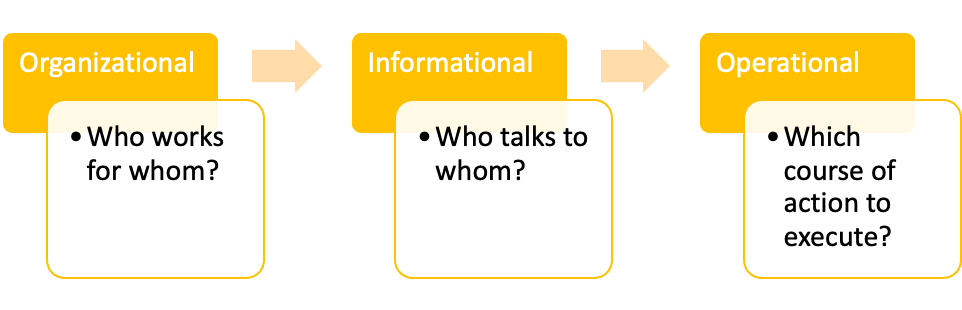

If decision-making is central to leadership, then how leaders decide, and how we teach decision-making, are crucial to a teams’ success. There are three broad categories that impact every decision:

- Organizational

- Informational

- Operational

Organizational decisions decide the “org chart” and designate who and what resources are in each part of the team. If you want a successful software development project to succeed, but assign no software engineers to the team, the project will most likely fail. Organizational decisions also specify the composition and leader of a team and designate authority and responsibility.

Informational decisions involve the flow of communications and designate who routinely communicates with whom. If situational awareness is low, the informational process may be at fault. To improve the communication flow in your organization, first understand which team members or subordinate leaders routinely communicate information to whom, and at what frequency, if these leaders are sending the information to the wrong person, then the process is inefficient or useless. And if the frequency of the communication is not correct, the right information will not arrive in time.

Operational decisions are the ones that most leaders understand as there is an obvious cause and effect when good or bad decisions are executed. Eisenhower’s decisions to launch D-Day invasion is an example of an extraordinary operational decision to solve a wicked problem. Elon Musk’s 2013 crisis, where he empowered nearly 500 employees to set aside their normal duties to design and produce Tesla cars, and switched their focus to close existing deals, was an extraordinary operational decision that paid off.

If leaders consistently make unsuccessful operational decisions, they should be re-trained or replaced.

Making it clearer to understand we can define these three decision categories as follow:

If your team’s organizational and informational decisions are faulty, even the best operational decision may not save the day. Effective leaders learn to align their team’s operational, organizational, and informational decisions to improve how the team decides, organizes and communicates.

Decision-Making Approaches

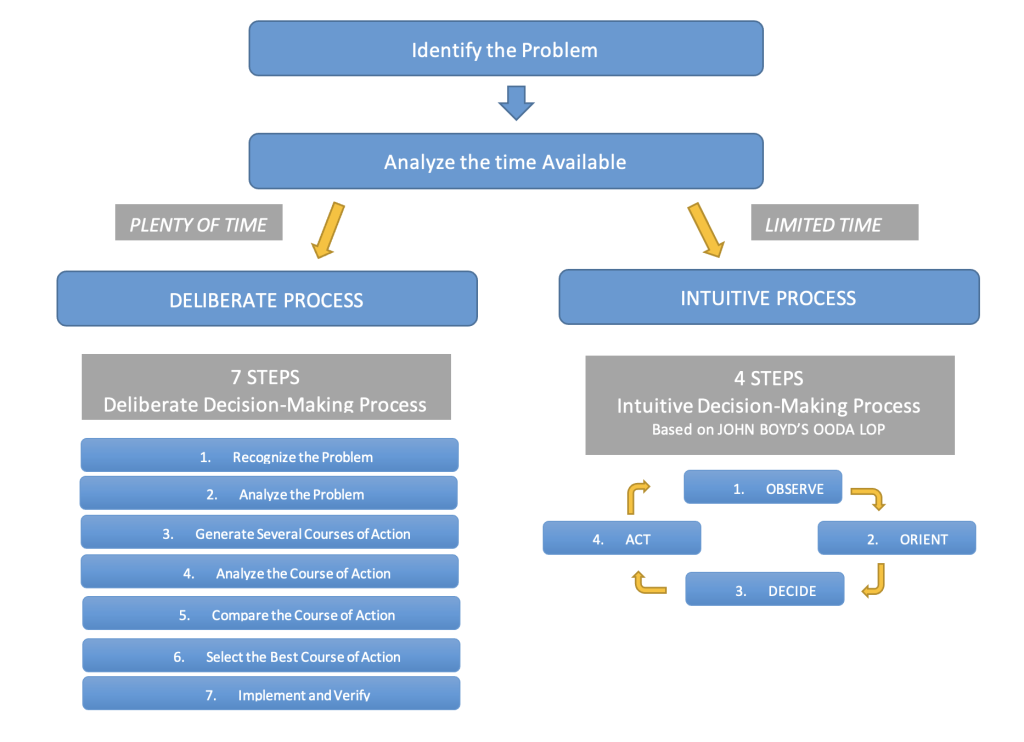

I will graphically show you the two primary methods of deciding and how the choice depends on the time available and the experience of the leader. The choice becomes easier if the leader has raised their awareness of decision-making, understand various approaches, and practices them.

In deliberate decision-making time is not critical. There is a sufficient time to conduct a deliberate analysis and course of action development. The situation is abstract with little pattern recognition. The level of experience of the leader and the team is low and there is a need to justify and “buy into” the decision. The situation requires explicit understanding of the people involved in the planning as the team and leader are new or inexperienced. There is no need to use planning sessions to resolve group conflicts or to find the optimal course of action.

In intuitive decision-making time is critical. There is limited time available to plan deliberately and there is an urgent need to find a workable course of action as soon as possible. Events are fast-changing, the situation is dynamic, but there are recognizable patterns occurring that a well-trained leader can identify. The level of experience of the leader and the team is high, and the leader is trained and confident. The team trusts the leader and they implicitly buy into the decision, understanding that a decision must be made in the time or the opportunity is lost. Also, there is little inter-group conflict and there is implicit understanding between the leader and the team. Finally, there is an un urgent requirement to decide quickly and apply a good enough decision in time to make a difference.

How to Plan

Planning is the skill to project your thoughts forward in time (when), space (where), and purpose (reason) to develop a course of action that will accomplish your goal. Planning involves the ability to visualize a situation, define a desired end state, and lay out effective ways to bring that end state into reality.

“With many calculations one can win; with few one cannot. How much less the chance of victory has one who makes none at all!” – Sun Tzu

In personal decision-making, business or war, your knowledge of yourself and your team, the situation, and your ability to use the time you have, form the basis for all actions. Once you understand all three elements:

- Yourself and your team

- The situation

- The time available

You now have the basis to develop an effective plan, and one way to address a planning is to clarify what you know. I call this the “Four Knows”:

- Know the situation and timing

- Know the environment

- Know yourself

- Know your competition

Leaders must learn to make decisions with limited information, Understanding the Four Knows raises your leadership awareness and can improve your plans. In chapter 6, of my Leadership Rising book, you can find all the complete guide towards making plans and decisions, I guide you through personal experiences and visual material in order for you to implement them on your personal and professional life.

Leaders show the team the path to success. They do this by planning and making correct, timely, decisions. Deciding is not easy, but it is much harder if you lack a mental framework to visualize how to decide; how to plan; how to communicate your intent to those you lead.

Join this Leadership journey, along thousands of other professionals like you, who are striving to rise to the level of their leadership, by subscribing to our free newsletter below.